An unusual mummified More than a century ago, the head has been discovered in Bolivia, which does not seem to be.

Research shows that actually a man’s remnant is considered, because of this it is from a different culture that was cut into the skull, possibly as part of a ritual, possibly as part of a ritual.

According to researchers, the new analysis is trying to keep the individual into the context of his archeology and “give them their local history”.

“These remnants are not just bones in any human reservoir,” a musicalologist and art historian Claire Barzone Science, directly, in the Cantonal Museum of Archeology and History in the city of Luzan, Switzerland. “They are the remains of people on their own.”

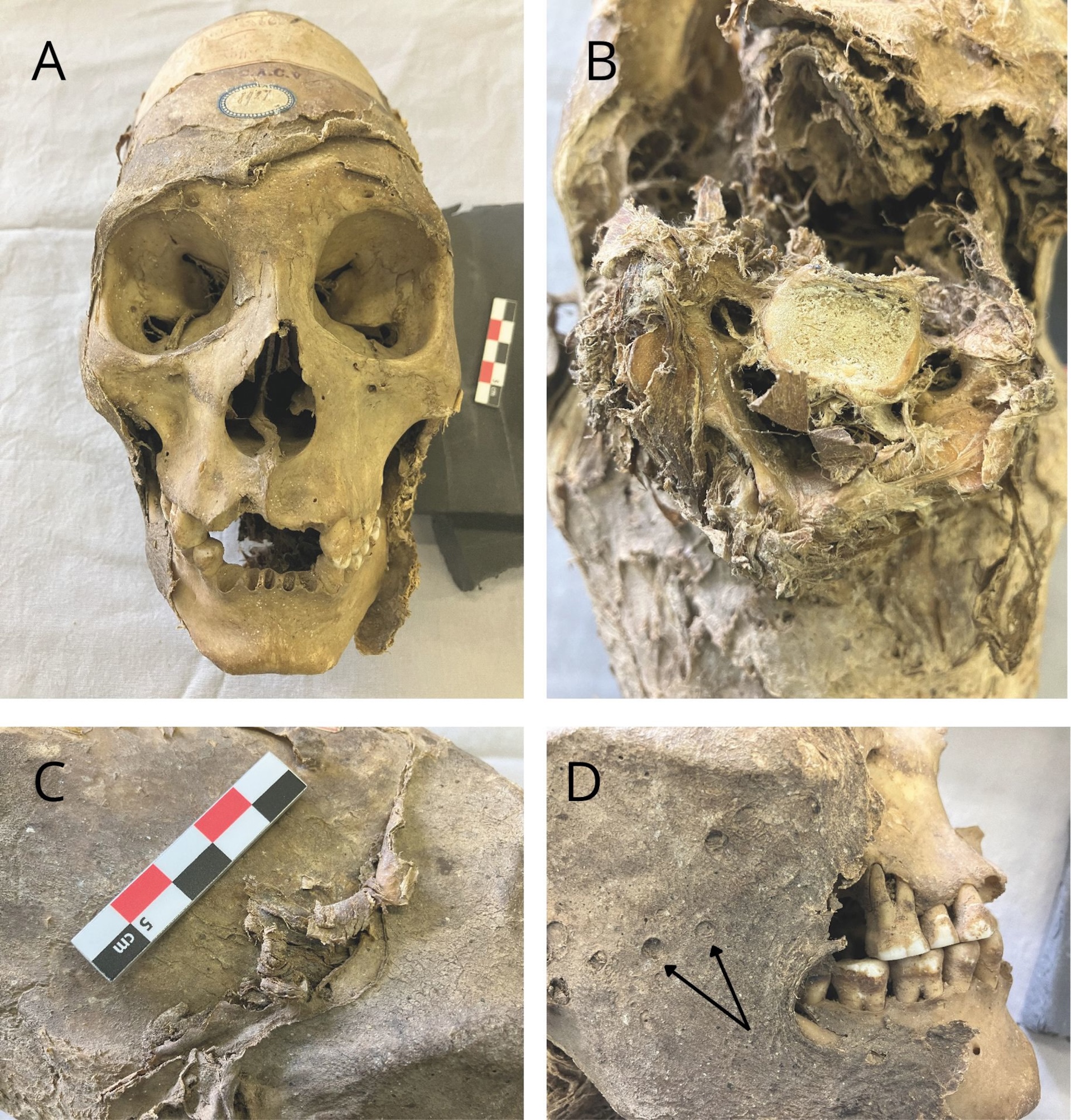

Berzon is the senior writer of a new study, published in the Lord on August 27 International Journal of Osteo ArcologyWho analyzed the mother’s head. It has some part of the skin, face, cranium, jaw and neck. The noteworthy thing is that the upper part of the head is almost con cons cones and is a prominent lesion from efforts Trapnection – The process of drilling or drilling from the cranium bone.

But there is no sign that the trapy was done in response to the trauma, which shows that it can have a ritual or social purpose.

Related: Inkas mastered in serious exercises of drilling holes in people’s skulls

Collect in Bolivia

The new analysis states that the head was from an adult who died at least 350 years ago and had done “cranial deformation” in childhood. Before Colombia, a relatively common common practice in South America, which had been firmly tied to a newborn child’s head.

In addition, for some reason, the upper right side of his skull was not completed. Researchers have written that deep cheeks were made in the outer layers of the bone, but it did not hole the inner layers.

The study also includes research on how the mamfied head was obtained through the museum and where it came from. Researchers found that the skull was donated by the Swiss collector to the Luzan Museum in 1914, which was acquired in Bolivia in the 1870s.

A note attached to the head said it is from one Their The person, however, found that the type of cranial deformation indicated that it was one of the indigenous groups living in the Bolivian Highlands, Emara.

The note also stated that a head was recovered in a particular area of Bolivia, which is now known where Emara lives. According to new research, it was probably taken from a “Cholpa” – a stone burial tower that was once common in the region – and possibly suffered naturally through the cold and dry climate.

Secure human remains

In keeping with their mission, researchers were careful about using only non -vicious methods of analysis – contrary to Radio carbon datingFor example, which often requires a small hole in an item to get the Enough of Enough enough to get enough content.

Since the dead person cannot give a consent, it was important to use an analytical method according to which what he could wish for, the study lead author Clauden AbigA humanitarian at the University of Geneva told the science directly.

In addition, devastating testing such as Isotopic or DNA analysis can be able to produce far more exact results than the methods used in the study, “but the decision should rest with the communities associated with them.”

For now, the museum is still in the museum collection, though it is not in public exhibition. Berzon said the museum had not yet received any request for returning home but was open to questioning.

Julia GreeskiA Paleopathologist who was not involved in the latest study at the German Archeology Institute but is Researched on traptins And the cranial deformation, directly told science that he had never seen a head that had tried the cranial deformation and effort.

In this case, there was no clear shock that could probably cause trouble efforts – though the mental disorders would not be able to leave any evidence on the skull – so it would have been performed for rituals or social purposes.

But there was no explanation as to why the trapination was not completed. “Maybe this person said, ‘I’m sorry, but I don’t want any more,” said Grassesi.