If Homo habilis was often stalked by leopards, it was probably not an apex predator. Credit: Built with AI (Dall-E 4)

About 2 million years ago, a young primitive man died near a spring near a lake in what is now Tanzania in East Africa. After archaeologists uncovered his fossilized bones in the 1960s, they used them to describe Homo habilis—the earliest known member of our own genus.

Paleoanthropologists largely describe the first examples of the genus Homo based on their large brains. There were at least three types of early humans: Homo habilis, Homo rhodolphins, and the best-documented species, Homo erectus. At least one of them built sites now in the archaeological record, where they brought and shared food, and made and used some early stone tools.

These archaeological sites date back to between 2.6 and 1.8 million years ago. The patterns within them suggest greater cognitive complexity in early Homo than has been documented in any nonhuman primate. For example, at Nyanga, a site in Kenya, anthropologists recently found that early humans were using tools that they moved up to 8 miles (13 km) away. This action indicates foresight and planning.

Traditionally, paleoanthropologists believed that Homo habilis, as the earliest large-brained humans, was responsible for the earliest sites with tools. It has been thought that Homo habilis was the ancestor of the later and larger-brained Homo erectus, whose descendants eventually led to us.

This narrative made sense when the oldest Homo erectus remains were less than 1.6 million years old. But given recent discoveries, it looks like a shaky foundation.

In 2015, my team discovered a 1.85-million-year-old hand bone in Oldovi Gorge, the same site where the original Homo habilis was found. But unlike the hand of this Homo habilis juvenile, this fossil looked like it belonged to a larger, more advanced, fully terrestrial rather than tree-based human species: Homo erectus.

Over the past decade, Newfoundland has continued to push back the earliest dates for Homo erectus: about 2 million years ago in South Africa, Kenya and Ethiopia. Taken together, these findings suggest that H. erectus is slightly older than the known H. habilis fossils. We cannot simply assume that H. habilis gave rise to H. erectus. Instead, the human family tree looks much more compact than we once thought.

What is the best way to find it all? Only one species of Homo is our probable ancestor, and perhaps only one could be responsible for the complex behaviors revealed at the Oldovian Gorge sites. My colleagues and I hit the road to test whether Homo habilis was top dog in Oldovi Gorge, so to speak, based on whether they were predators or prey.

Who was hunting?

In Oldovi Gorge, there is abundant evidence that early humans were eating animals as large as a gazelle or even a zebra. Not only did they hunt, but they repeatedly brought these animals back to the same place for communal use. This is the concept of a “central supply place”, much like a campsite or home today. Dating back to 1.85 million years ago, it is the earliest evidence of frequent meat-eating and early humans regularly acted as hunter-gatherers rather than prey.

All animals occupy a position on the food web, from top to bottom. High-level predators, such as lions, are not usually hunted by low-level carnivores, such as hyenas.

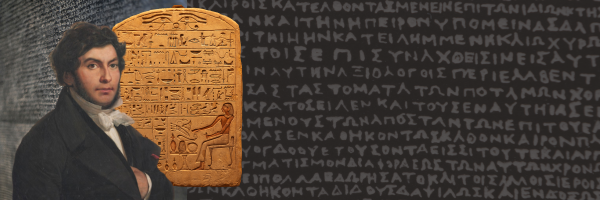

(a) OH7 obligatory with two dental pits. (b) OH65 maxilla enlarged in tooth pit. Credit: Royal Society Open Science (2025) doi: 10.1098/RSOS.250548

If Homo habilis was obtaining large animal carcasses, either by hunting or by scavenging lions from their kills, it seems logical that these hominids could effectively deal with predation threats. That is, a predator is usually not the hunted.

In the African savanna, top predators such as lions do not usually die from attacks by other predators. Humans still occupy a top predator niche: for example, the Hadza hunter-gatherers in Tanzania not only hunt game but also keep lions from killing them, and successfully defend themselves against attacks by other predators, such as cheetahs.

But, if Homo habilis wasn’t yet an apex predator, you’d expect them to occasionally fall prey to lower-food-chain carnivorous cats—such as cheetahs.

The best-known human fossils from this stage of evolution bear traces of carnivore damage, including the two best-preserved H. habilis fossils from Oldovi Gorge. Was it caused by a scavenging carnivore, after death? Or did a big cat at the top of the food chain kill these early humans?

My colleagues and I set out to solve the question of which predators got their teeth on H. habilis and most likely. That is, before or after or after the death of ancient humans.

AI suggests that H. hibelius was not an apex predator

This is where artificial intelligence comes in. Using computer vision, we trained on hundreds of microscopic images showing the tooth marks of the main carnivores in Africa today: tigers, leopards, hyenas and crocodiles. The AI learned to recognize the subtle differences between marks made by different hunters and was able to classify the marks with high accuracy. The work has been published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

When we combined the different AI approaches, they all pointed to the same conclusion: the tooth marks on the Homo habilis bones matched those made by a leopard. The size and shape of the markings on the fossils of these two early Homo habilis individuals, as well as their orientation when feeding on prey.

Our discovery challenges the long-held view of Homo habilis as a highly skilled toolmaker, hunter and carnivore.

But perhaps that shouldn’t be too surprising. The only complete skeleton of this species found in Oldovi Gorge was that of a very small individual – just 3 feet long (less than 1 meter) with a body that still showed characteristics suitable for climbing trees. It hardly matches the image of a hunter capable of bringing down large animals or stealing carcasses from lions.

If it wasn’t Homo habilis to accomplish these feats, it was probably Homo erectus, a larger species with a larger body and more advanced anatomy. But this opens up other mysteries for future researchers: What was Homo habilis doing at the Olduvian Gorge archaeological sites if we weren’t responsible for the hunting tools and symbols found there? Where exactly did Homo erectus come from, and how did it evolve?

My team and others will return to places like Oldovi Gorge to ask these questions in the coming years.

More information:

Manuel Dominguez-Rodrigo et al., Meta-learning analysis of tooth marks on bone provides a robust framework for understanding taxonomic carnivore agency: examining the role of feldspars as predators of Homo habilis, Royal Society Open Science (2025) doi: 10.1098/RSOS.250548

Provided by Conversation

This article is reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Reference: AI Reveals Predators Chewed Bones of Ancient Humans (2025, October 28) Retrieved October 28, 2025, from https://phys.org/news/2025-10-reveals-predators-ancient-humans.html

This document is subject to copyright. No part may be reproduced without written permission, except in fair cases for the purpose of private study or research. The content is provided for informational purposes only.