Virtual reconstruction of the Murgon paleoecosystem during the early Eocene, 55 Mya. Image created with Google Gemini A. It has also been shown to be one of the most abundant soft-shelled turtles. In this ancient lake, the sediments forming the fossil deposits accumulated. Credit: University of New South Wales

In the backyard of a local grazier in the small south-east QLD town of Murgon, scientists have been digging for decades into what looks like an undisturbed mud pit. But deep within the soil is one of Australia’s oldest fossil sites. This is a window when the continent was still connected to Antarctica and South America.

Now, an international team led by the Institut Cataltología Michel Croissafont (ICP), including researchers from UNSW Sydney, has revealed the oldest crocodile eggshells ever found in Australia. Published in work Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

The fragments, named Vaculolithus godthelpii, once belonged to the Mesozoan crocodiles. This group of now-extinct crocs dominated inland waters 55 million years ago. Modern saltwater and freshwater crocs arrived in Australia only later, around 3.8 million years ago.

“These eggshells have given us a glimpse into the intimate life history of mecosuchines,” says Xavier Panades I Blas, lead author of the study.

“Now we can investigate not only the peculiar anatomy of these crocs, but also how they reproduced and adapted to changing environments.”

From swimmers to tree-climbing predators

Unlike today’s saltwater and freshwater crocodiles, mycosuchians filled strange ecological niches.

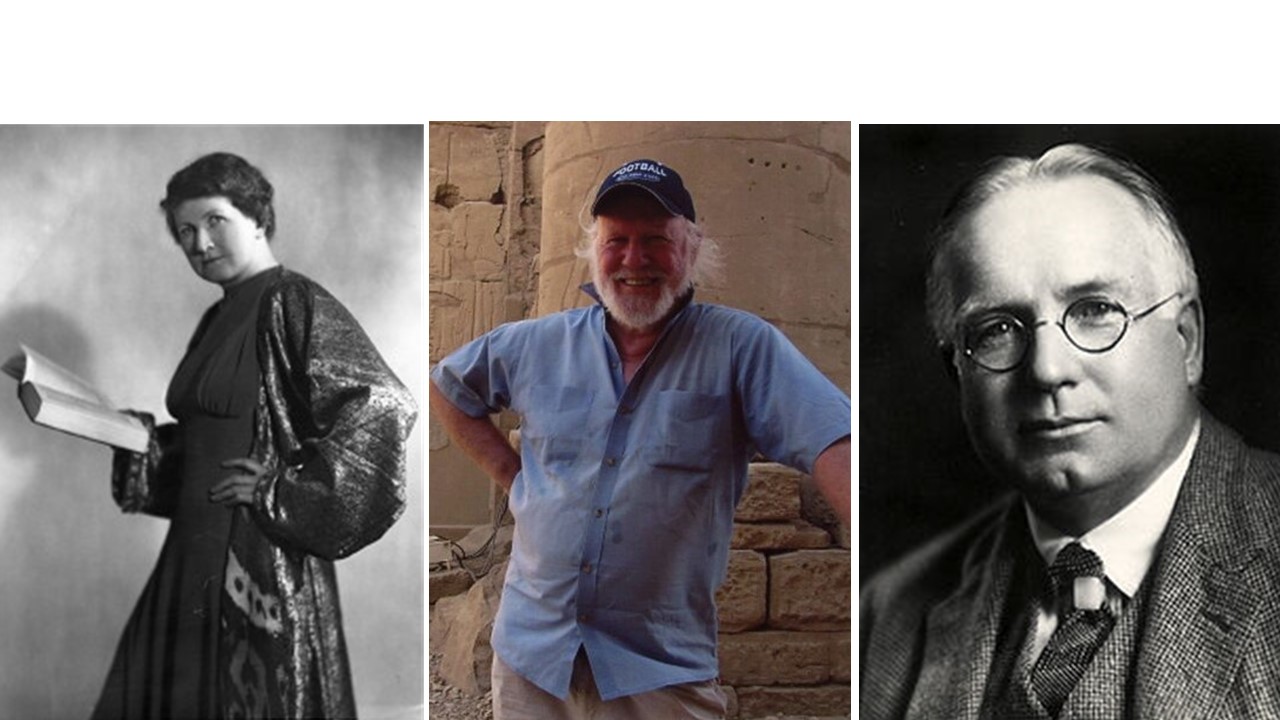

“It’s a strange idea,” says UNSW expert Professor Michael Archer. “But some of them were terrestrial predators in the forests.”

They say there are hints of this in a wide range of small Mesozoic fossils previously discovered within 25-million-year-old deposits from another region: Budjamula National Park on the Wani Country in north-west QLD, the River World Heritage Area.

Professor Archer says some of the river species there have grown to be at least five meters tall.

“Anything apparently at least partially semi-jewelry was also ‘dropcrocs,'” he says.

“They were probably hunting like leopards.

A fragile time capsule

Eggshells are an underutilized resource in vertebrate paleontology, says Panadès I Blas.

“They preserve microstructural and biochemical signals that tell us not only what kind of animals they laid, but also where they nested and how they bred,” he says.

“Our study shows how powerful these fragments can be. Eggshells should be a routine, standard component to be collected, prepared and analyzed alongside bones and teeth.”

Fragments of murgun shell were examined under optical and electron microscope. Their microstructure suggests that crocs lay eggs on lake margins, adapting their reproductive strategy to fluctuating conditions.

Co-author Dr. Michael Stein says the Mesosuchian crocs have lost much of their hinterland to encroaching land—not only do they have to compete with new Australian arrivals in shrinking waterways, but their megafaunal-sized prey also continue to decline.

Dr. Steyn says that Margoon Lake was surrounded by a lush forest.

“The forest was also home to the world’s oldest songbirds, Australia’s oldest frogs and snakes, a wide range of small mammals with South American links, as well as one of the world’s oldest bats,” he says.

A story with teeth

Professor Archer says the discovery within the Tangamara deposit at Murgon is part of a bigger story. One that enriches the understanding of ancient ecosystems before Australia became an independent continent.

In 1975 they find a fragment of a strange crocodile jaw in the Texas Caves of south-east Queensland.

Although it has since been confirmed as a Mesosuchian croc, it seemed so strange to Professor Archer at the time that he did not suspect it was a crocodile. It looks like a reptile—but with teeth like a dinosaur. He was so puzzled that he decided to consult Professor Max Hecht – a reptile expert at the American Museum of Natural History.

“Max dropped his coffee cup nearby when he saw it,” Professor Archer says. “It resembled another species of extinct croc with dinosaur-type teeth found in South America. This was the first realization that crocodiles with such teeth were also part of the old record in Australia.”

Professor Archer says he and his colleagues have been excavating in the Murgon area since 1983, literally in the backyards of enthusiastic locals.

“This year, UNSW colleague Hank Goodhelp and I drove to Murgon, parked the car on the side of the road, grabbed our shovels, knocked on the door and asked if we could dig up their backyard,” says Professor Archer.

“After explaining the prehistoric treasures that might lie beneath their sheep paddocks and that fossilized turtle shells had already been found in the area, he smiled and said, ‘Of course.’

“And, quite frankly, with the many interesting animals we’ve already found in this collection since 1983, we know there will be many more surprises to come with further digging.”

Awareness of protection

For Professor Archer, such discoveries are little more than glimpses of a vanished past – he sometimes reminds us that Australia’s fossil record may hold important clues about how to save some of today’s threatened species.

He is working with a multi-institutional team on the “Bramis Project” to bring the mountain pygmy possum—Broramys paros—back from the brink of extinction.

Native to the alpine regions of eastern Australia, this species is critically endangered as climate change pressures increase. However, Professor Archer’s team discovered that its prehistoric relatives, which have been evolving for the past 25 million years, have always thrived in low-lying rainforests, including those that covered riverine areas between 25 and 12 million years ago.

This led to the theory that the immediate ancestors of today’s mountain pygmy possum followed the rainforests when they moved into alpine regions during a warm, wet interval during the Pleistocene epoch. But when the climate in the alpine zone changed and cooled, they had to develop invasive behaviors like hibernation to survive the increasingly inhospitable conditions.

A few years ago, Professor Archer’s team, working with Trevor Evans, manager of the Secret Creek Sanctuary, and with donations from several organizations, including the Prague Zoo in the Czech Republic, built a breeding facility in a non-alpine rainforest area near the city of Lithgow.

Today, mountain pygmy possums thrive within this non-alpine sanctuary. Just as Professor Archer says the fossil record predicts they would.

As climate change increasingly threatens the existence of more and more species, he says, not all stories about the gloom and doom of climate change disasters are needed.

“The Bramis project is a demonstration that, at least in some cases, we can develop strategies to save endangered species,” says Professor Archer.

“Clues from the fossil record matter,” he says. “Not only to understand the past, but also to help secure the future.”

More information:

Xavier Panades I Blass et al., Australia’s oldest crocodilian eggshells: insights into the reproductive paleoecology of mecosuchines, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (2025) doi: 10.1080/02724634.2025.2560010

Provided by the University of New South Wales

Reference: Australian ‘drop crocs’ unlock insights into ancient ecosystems (2025, November 11) Retrieved November 11, 2025 from https://phys.org/news/2025-11-crocs-crocs-insights-encient-ecosystems.html

This document is subject to copyright. No part may be reproduced without written permission, except in fair cases for the purpose of private study or research. The content is provided for informational purposes only.