In September 1822, something unusual happened. A young French scholar named Jean-François Champollin bursts into his brother’s office in Paris, exclaiming, “Ge tenis som affier!” (I’ve got it), and immediately fainted from the shock. He will not fully recover for five days.

What did he do? After decades of scholarly struggle, Champollion had finally cracked the code of Egyptian hieroglyphs, a language that had been silent for nearly 1,400 years. His achievement began in the birth of modern Egypt.

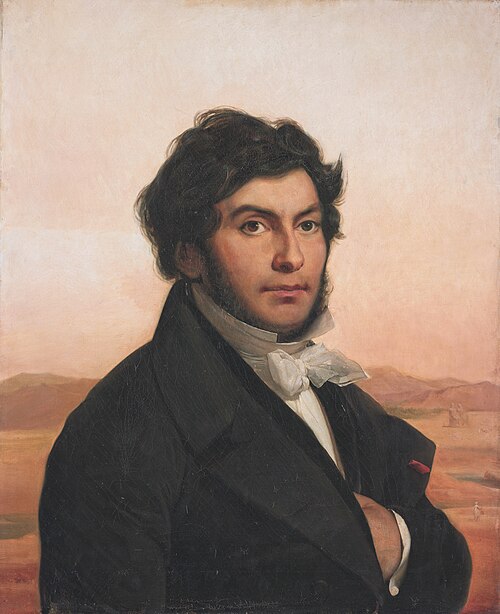

Jean-Francois Champollin, by Lavon Coguet

Progress that speaks for the ancients

Champlain’s prudence was more than academic triumph. It roared back to life a lost civilization. Temple walls, tombs, and ancient papyri, once silent, can finally speak again.

But this was not an isolated moment of genius. It was the result of more than 20 years of intensive study, academic rivalries and collaborations. And at the center of it all stood the Rusta Stone, a modest-looking slab of black stone that captivated Europe’s greatest minds.

The discovery that changed everything

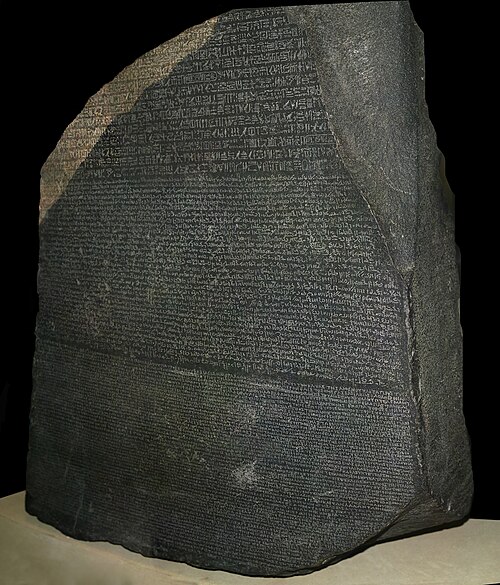

The Rosta Stone was discovered on July 15, 1799 by French soldiers rebuilding a fort near the town of Rosta, now Rashid. Embedded in the wall, the slab bore an inscription in three scripts: hieroglyphic, demotic and ancient Greek.

Display on Rusta Stone at the British Museum in London

Although the British captured the stone in 1801 and brought it to the British Museum, the French had already made castes and rubs, allowing scholars from across Europe to examine it closely.

The inscription? In 196 BC, King Ptolemy V. An edict issued in honor of dozens of such orders was created, but this one was special because it repeated the same text in three scripts. This gave scholars a real chance to unlock the ancient language.

What did the stone reveal?

The Greek section, then the only legible one, covered 53 lines. The demotic text contains 32 lines, and the hieroglyphic portion, although damaged, preserves the essential 14 lines. These fragments became the basis of all serious attempts to decode the mysterious symbols of ancient Egypt.

Scholars who contributed

Champlain was not alone in this race. Many brilliant minds helped develop the Earth.

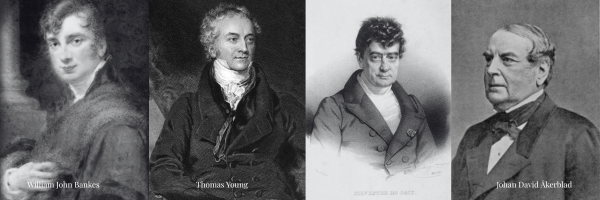

John David Eckerblad, A Swedish diplomat and linguist, worked under DCC and succeeded in identifying proper names and creating a partial demotic alphabet. Many of his predictions turned out to be correct.

Silvestri de Sisione of France’s leading linguists, taught both Sacréblad and Champollin. He made some early progress with Demotic, but later clashed with Champoline with Credit Over Credit.

Thomas Young, A British polymath, was the first to publish a partially correct translation of the Rosetta Stone. He identified a number of names and phonetic values. Although Champlain built on his work, it gave the young man little recognition.

William John Bainesan English collector and adventurer, brought home a bilingual obelisk from Philly’s temple. Its inscriptions, including the name Cleopatra, provided important context for Champlain’s decipherment efforts.

Scholars participating in Rusta Stone

The Genius of Champoline

The son of a poor bookseller, Champlain had an unparalleled gift for languages. By his teenage years, he had mastered Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and Coptic—the last form of the ancient Egyptian language.

His knowledge of Coptic was key. By comparing hieroglyphs with their Greek equivalents and Coptic roots, he realized that the symbols were not purely symbolic, but also phonetic. In September 1822, he presented his findings to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres. His letter, Letter à M. Dasser, became a landmark publication in Egyptian history.

Hieroglyphics in the Grand Egyptian Museum 101 Names of Kings

Although Champlain died of a stroke in 1832 at the age of 41, his work opened the door to modern Egypt.

Legacy in 2025

More than 200 years later, Champlain’s decision remains a source of trouble. Thanks to his work and the scholars who came before him, we can read religious texts, tomb biographies, and administrative records thousands of years ago.

This development reshaped our understanding of the world’s greatest civilization. Indeed, the 1822 decision set the stage for future discoveries, including Howard Carter’s momentous discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb exactly 100 years later.

Learn to read ancient hieroglyphs yourself

The story of how Champollion and others cracked the ancient Egyptian code is truly thrilling – but here’s the best part: Now it’s your turn To join the ranks of modern day code breakers.

It’s one thing to read about Champlain’s incredible success – but nothing compares to cracking the code yourself.

That’s why I’m inviting you to join me for a special online course I’m teaching this June:

Hieroglyphs Decoded: Read and Write Like a Pharaoh

Over the course of three lively and accessible classes, I’ll guide you through the essentials of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs – from reading royal names to writing your own.

Tuesday: June 3, 10 and 17, 2025

4:00 pm to 5:30 pm EDT

Live online + full replay and content included

Find out more here