In 1545 in Now in the northwest of Italy, a woman named Isabella Della Wulp, a Dachi, became pregnant. When she approached the whole period, Isabila suffered something that was then called a barrier to the brain – possibly a paralysis – and she died. His midwife found out that the baby was still alive, and his audience pressured the physician to provide routes to the Caesen section. But he refused, and when a barber surgeon arrived to cut the baby, it was too late: a little girl named Kimla lived only a few minutes. Among the horrors, though, humanity and sympathy were: “The women who surrounded Isabila in their last days showed independence and sympathy in trying to save their daughter.”

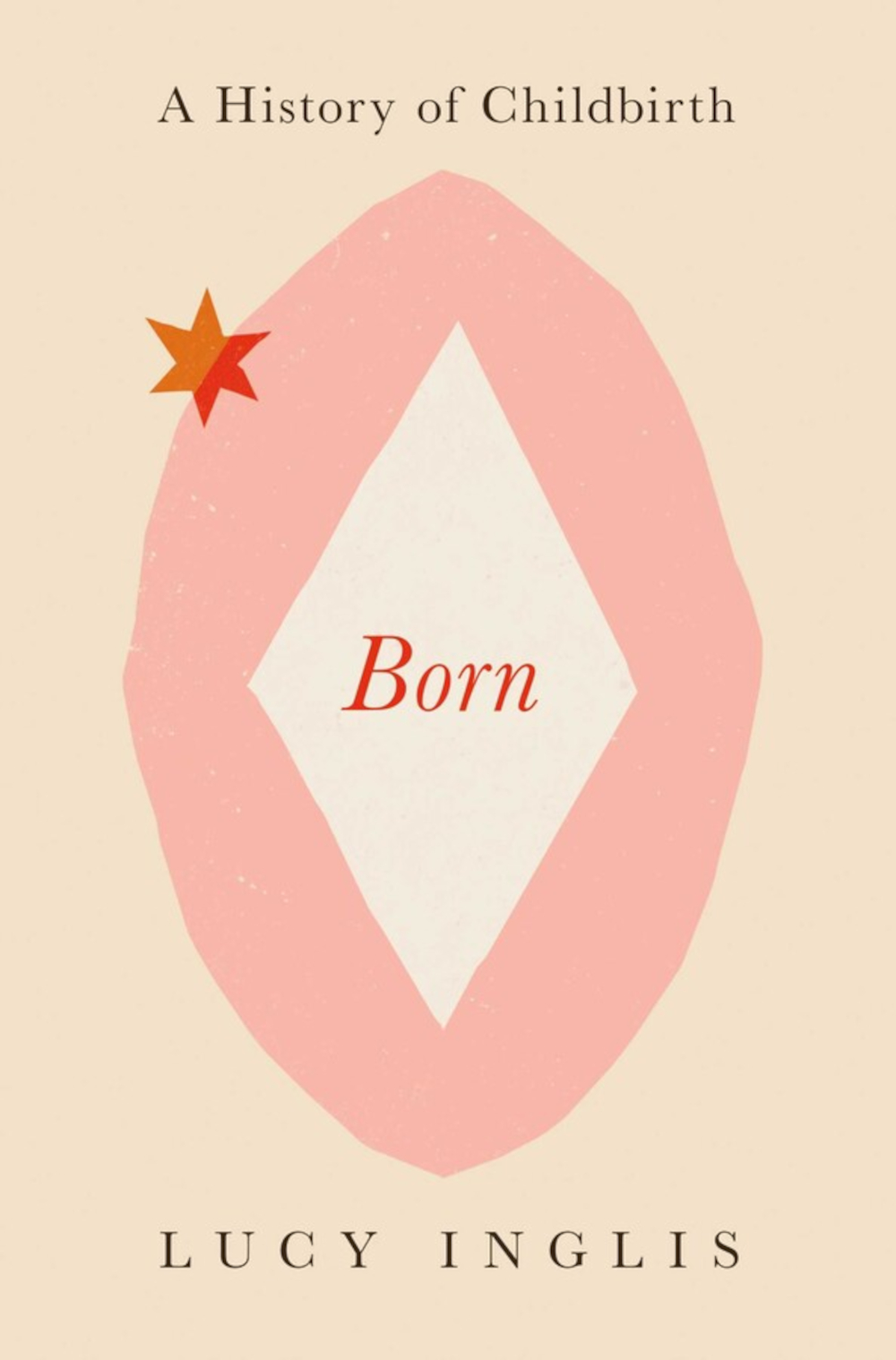

For every Isabella, whose story was recorded in extraordinary detail, there are billions of other women who have experienced pregnancy and childbirth suffering, risk, sorrow, love, and sectarian happiness. This is the history of social, medical and feminine history that historian Lucy Angle presents the chronic in his latest book, “Borne: The date of birth date”. Angleis started his career blogging and writing about Georgian London, following a book about the history of opium. In “Borne”, they continue their tradition of examining the broom of human history through an extraordinary lens: the worldly and still extraordinary process through which humans are considered and emerged in the world. His book is involved in the recent work work, such as Kate Bohan’s “Eve”, which examines human history through an intimate women’s lens.

The book review B (b (b ( “Borne: Birth Date,” by Lucy Angleis (Pegasis Box, 336 pages).

Angle writes, “The story of how we are born is the story of all of us, and so we should go back to the beginning,” his story begins during the upper palecthack, tens of thousands of years ago, the era in which archaeologists have the history of our first evidence of the birth of the child’s birth. It continues through the birth of children’s experiences and cultures about the experience and culture of children, in which jeansing and mirror have suggested pregnant women in Mesopotamia, one of the oldest sculptures in the world, up to the Venice of Hohal Philus. This is a 2.4-inch sculpture that was discovered in the German city of Sobia, depicting a woman who is shown to a woman who “looks like more wounds than sexual organs,” Angle’s observed, and spreads her legs-after “a real” woman.

In some cases, the book of England is a history of technological development. During this story, we learn about many parties. The first recorded pregnancy test is from ancient Egypt, where women used to urinate in a bag of bags and wheat to find out if they are pregnant or not pregnant with the boy, a girl. For the first time, the history of the oral contraception is from the North African Greek city of cylinde, where women have made a clear herb now a Salafone to control their fertility. The first ethnic manual was written in ancient Rome, and possibly the first speculation and forces belong to the Islamic Spain.

A maritime change occurred in the middle of the last thousand, when the understanding of the birth of the West intensified with the “literary culture of the Middle Ages, the sudden growth of science and medicine and the invention of machine”. After that, for the first time, the sharp arrived. In Switzerland, a sower may have performed the first successful section of his wife in 1500. Doctors presented the first Ether in pain in the 1840s, the second Rif in the RIF war was invented by a Spanish military doctor in the early 20th century, and the first baby was born in Vitro Fertilization in 1978.

But the story of English is far from the traditional explanation of new technology. During the birth of her child’s birth, she offers a social history of gender character, medical authority and physical sovereignty. “Borne”, in three topics, all heartbroken for modern readers, resonate, repeatedly harvest. First of all, the idea that a “natural” and “unnatural” method of approaching the birth of a baby is a false two -way, which shows about 500 500 years to claim that the C -section was brutally because the Antichrist was born. Second, the debates around it, whether it is acceptable for women to take medicine medicine during labor, is acceptable to the advent of Christianity, and for example, the example of its example and ethical reaction and ethical reaction, which was allowed in the early 20th century, in the early 20th century. And third, the rise of a medical profession that eliminates masculine knowledge at the expense of women’s experience, to raise the new position of the doctor and deny the old midwife. As English writes, “The ultimate irony of this masculine dominance of women’s regeneration is that men do not experience any of the pregnancy or the birth of a baby.”

Unfortunately, another resonance for modern readers is a dangerous consequences and humiliating horror that has already surrounded the birth of a baby. It is surprising to read “Borne” how the human race survived. For example, Angles expressed the happiness of industrial London, where sun and nutritional women died in Dangi hospitals as the rackets had correctly shaped their pelvis. In most parts of history, death touched all women, regardless of the social class: Despite their education, their intelligence and their wonderful work, both Mary Wilston Craft and Mary Shelley died in the birth of Purepal fever, doctors did not wash their hands.

Angle also describes even more disturbing horrors: in the name of a major ideal, as a result, corruption by people against each other. Some of these examples come from ancient and medieval worlds, such as the act of “exposing” children, or the fear of more populations, are left to die. But many people are from enlightenment or recent history. England Jay Marwin writes about the Sims, the person who invented modern speculation and underwent surgery, but experienced these progress by experimenting with women in the Self -South. She launched similar programs in India in the 20th century, along with the development and mass sterilization of “disqualified” in the United States, as well as in the 1950s through the so -called donor gentlemen, and continued well by the local government until the 1970s. And in her last chapter, she mentions the death of Amber Nicole Thorman, who was killed by Sepsus at a Georgia hospital in 2022, thanks to the laws of anti -abortion.

If we do not continue to improve the material conditions of our brave mothers, Anglis writes, “This is not science that will fail us.”

The English book is not without its flaws. Our knowledge of birth methods is limited during pre -history and even during antiques, and, perhaps due to personal prejudice towards recent history, the initial chapters felt thin. Another problem arises from the fact that the date of birth is linked to it, well, from everything that causes the story of Anglis to feel incredible: the spread of smallpox in the United States, the history of the industrial revolution, the trials of the Salem Witch, the Armenian genocide, and the Nazis about the brutality of the Nazis, and the Nazis.

Nevertheless, however, Angle’s landing sticks, and about it practically ends with the call, because when we continue to form our birth date, we should not accept the most conditions. As history goes ahead, if we do not continue to improve the material conditions of our brave mothers, I write, “This is not science that will make us fail.”

As we look at the future, she says, “At the right time and in terms of choice, the right to give birth to a suitable place, because of unnecessary interference by strangers or governments, we must fight to establish and maintain.”

Emily Katano is a New England writer and journalist whose job has been published in Slate, NPR, Bafler, and Atlas Ozbkora, among other posts.