By Laura Ranieri Roy

Here’s a story that might feel like a Hollywood script. A glittering jewel, a trick within a job, and a lost treasure. think The pink pantherfor , for , for , . To catch the thiefor Ocean 8. But this is a real one. Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

On September 9, 2025, a A 3,000-year-old bracelet from Pharaoh Amenemope Disappeared. The theft was not encouraged by masked thieves at night, but by someone inside the museum’s conservation laboratory in broad daylight.

Double? The details are ridiculous. Was it diseased? Did he do the old… “hey, look over there” trick??? Whatever, it worked. Within hours (and after calling his black market jewelry friends), he smuggled the bracelet out of the museum and sold it in Cairo’s goldsmiths district. Thankfully, three people have now been arrested.

Melted for pennies on the dollar

The trail of this priceless artifact is surprising and tragic. The conservator reportedly brought the bracelet to a friend in Cairo’s Al-Sida Zainab district, who owns a silver shop. From there, it reached the owner of a gold workshop in Al Sagha, the historic goldsmith district. In the end, it landed with a stinking gold worker, who melted it down to be remade into other goods.

Price? A mere EGP 194,000About oth out ,000 USD 4,000.

It wasn’t just any trinket. The bracelet was a The solid gold band is studded with lapis lazulidating to around 1000 BCE. It may not have been the most elaborate piece of tennis, but as a rare royal antique, its historical and cultural value was beyond calculation.

Authors photo under Cairo Museum – Renovation 2016

,000 US$4,000: a full year’s salary for many people in Cairo

It is difficult for many of us in the West to understand why anyone would risk their career and freedom for such pettiness. But in Egypt, even for a qualified museum conservator, $4,000 can represent a salary of more than $4,000 a year.

Here’s what conservators in Cairo typically earn:

- Medium Conservator: EGP 15,000–30,000 per month (≈ 310–$620 USD) → $3,700–$7,400 USD per year.

- Senior / Head of Department: EGP 400,000–630,000 per year → $8,250–$13,000 USD.

- Museum Curator (Relevant Field): EGP 255,000–266,000 per year → USD 5,250–$5,500.

In this light, theft has a painful social dimension. Poverty, low wages and limited opportunities make even skilled professionals desperate.

History is repeating itself

This is not the first time that Egypt’s treasures have been looted. In fact, theft echoes a long tradition that stretches back to ancient times.

After the glory of the New Kingdom, Egypt entered a period of decline. During the reign of Ramesses III (twelfth century BCE), wars against mining expeditions and raids on “sea people” and lavish spending on temple renovations depleted the treasury. The workers at Deir el-Medina—the artisans who built the royal tombs—were unpaid and hungry. His grievances have led to history First labor strike recordedpreserved in the strike papyrus at the Oriental Institute in Chicago.

Within a century, tomb robberies intensified Valley of the Kings. Who better to know where the treasures were hidden than the gravediggers themselves? Gold, silver, and jewelry were looted, melted down, and sold on the black market.

Fast forward 3,000 years: A conservator, with intimate knowledge of museum procedures, targeted the bracelet. Different millennia, same story.

Amenemope: Pharaoh behind the bracelet

So who was Amenemope, the king whose bracelet is now lost?

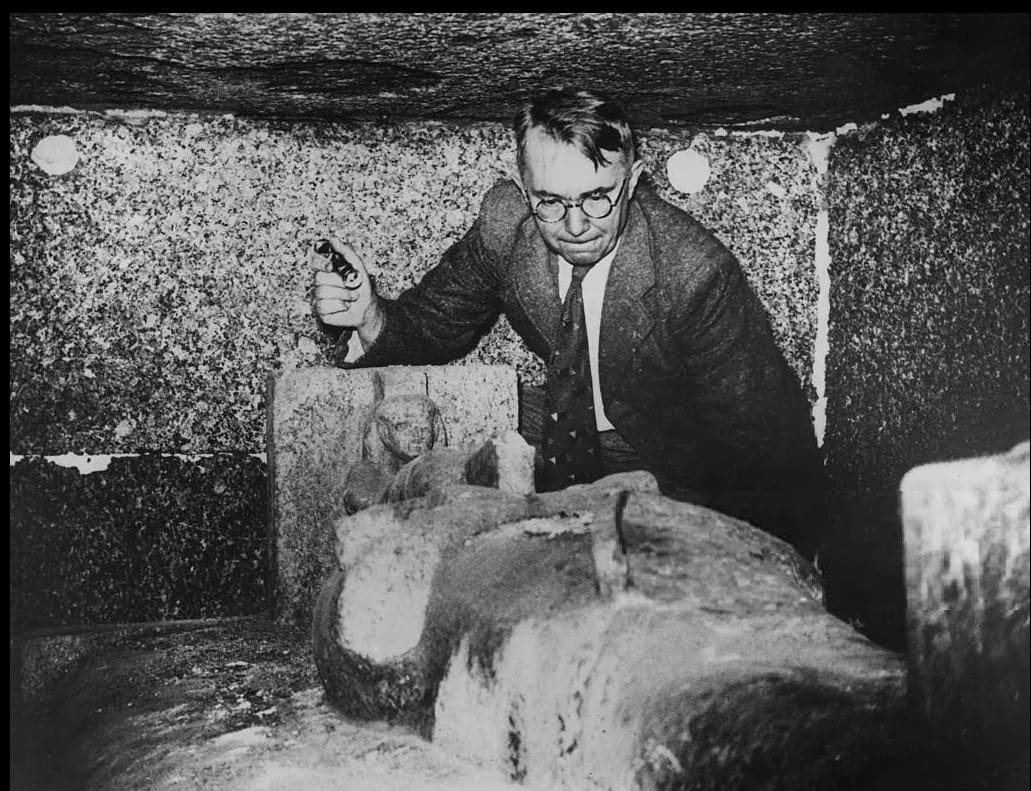

I (author’s photo) with a gilded mask of Amenemope – and bracelet

Amenemope ruled Egypt for about nine years 21st Dynasty (c. 1001–992 BCE), was its capital for part of the turbulent Third Intermediate Period. Tennisfar to the north in the Nile Delta. Tennis may be familiar to film people: I Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Arkit was envisioned as the secret resting place of the Ark of the Covenant.

In fact, tennis was a “second-hand capital”. Its rulers recycled monuments, obelisks and even coffins from earlier periods. Still, Amenemope’s burial contained real treasures Gold and lapis bracelet And a beautiful one Gilt funerary mask.

Pierre Montet, the French archaeologist discovered the treasure of tennis c) Wikipedia

The tomb was discovered by French archaeologists in the late 1930s Pierre Montetwhich revealed four nearly intact royal burials at Tens: Psusennes I, Amenemope, Shoshenq II, and General Wendjebauendjed. The find was surprising – on par with Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun. But timing is everything. In 1939, Montet’s declaration was called into question by the outbreak of World War II.

Today, the tennis treasures form an outstanding part of the Egyptian Museum’s collection. Look at me Video on the magnificent silver casket Shushak I

-

Authors photo: Gold Silver Presentation Bowl Tennis Treasures

-

Authors photo: Silver casket Shoshanq i

-

Author photo: More tennis treasures

Cairo Museums in Transition

The theft itself sheds light on the Egyptian Museum. Opened in Tahrir Square in 1902, it has long been a beloved, if somewhat chaotic, temple of antiquities. Its wooden cases, echoing halls, and 19th-century charm charm visitors—but its security measures often fall short of international standards.

As Egypt prepares to reopen Grand Egyptian Museum (Mini) Near the Giza Pyramids, the Tahrir Museum has been slowly moving objects. Just this month, Tutankhamun’s last treasures, including his famous golden mask.

But in the conservation lab, where the Amenemope bracelet was kept, they were reportedly there No security cameras. This absence of supervision has enabled theft.

Questions that remain

The loss of the bracelet suggests some good reflections:

- Is the real reason for such thefts is Egypt’s struggling economy, which makes even skilled workers vulnerable?

- Should Egypt’s ancient museums adopt the same strict protocols – environmental, security and procedural – as those in Johor?

- And what should the world demand? Antiquities returned to Egyptwhen its institutions sometimes struggle to protect what they already possess?

A loss, but not the last

The story of Amenemope’s bracelet is both tragic and strangely familiar. For five millennia, Egypt’s treasures have been stolen, smuggled, melted down or hidden. This theft is just the latest chapter in a cycle of looting and protection that seems to be woven into the nation’s history.

We can only mourn the loss of this piece of ancient craftsmanship. It is a golden ring that once adorned the wrist of Pharaoh. For a fleeting profit of $4,000, the world is robbed of a link to its deep past.

And as history shows, it won’t be the last time.

###